“We Accept Of Course That It Is Draconian: And Deliberately so”.

Former Ambassador, Human Rights Activist

On Friday 4 July I headed back to the Royal Courts of Justice for the hearing brought by Huda Ammori, a co-founder of Palestine Action, on an application for relief from the proscription order against Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation.

Huda had applied for judicial review of the legality of this order. There is to be a hearing on whether a judicial review will be granted in the week beginning 21 July. What Friday’s hearing was about, was whether the proscription should be suspended until that hearing on whether permission will be given for judicial review.

This is called interim relief.

The legal precedents on interim relief are that this question should depend on three points.

The first is the probability that a full judicial review might ultimately succeed, in other words a preliminary assessment of the merits of the case.

The second is whether irremediable damage will be done to anyone in the meantime if the order is not suspended, should the result of the process eventually be a successful judicial review.

If those two hurdles are passed, the third is whether on a “balance of convenience” the irremediable harm that might be done if the Order is not suspended but ultimately is set aside on review, is worse than the irremediable harm that the public might suffer from losing the benefit the government intend by the Order in the interim, should the judicial review be denied or eventually confirm the legality of the Order.

At this stage I presume you are deciding whether to bother to read that six times until it makes some sort of sense, or whether this is going to be an impenetrably dull article full of arcane legal nonsense and you would rather browse something else.

I do sympathise.

On Thursday I had spent the train journey down from Edinburgh trying to get my head round all this; at one stage I had a lovely tourist couple from Hungary, who had the bad luck to share the train table with me, each kindly holding sheaves of documents and using their thumbs as placeholders.

I rose at 6am on Friday to ensure I would get into the courtroom. I was anticipating that, as with the Assange hearings or the ICJ hearings on Genocide, there may be a long queue wating to enter. In fact there was nobody at all at 7am except me and a great many policemen.

I had a coffee opposite the court building, and a constant stream of policemen came into the coffee shop to buy coffee and doughnuts. By 07.45 there was not a doughnut left within a mile of the Strand.

Anthropologists should study this. British policemen have no history with doughnuts. They never occupied any place in Metropolitan Police culture. However a continual barrage of American films and television programmes portray policemen as doughnut eating; so presumably British police think this makes them cool. In fact it makes them fat.

I shall not be paranoid about the fact the police kept photographing me as I hung round waiting for something to happen. They had nobody else to photograph. I tried to think of things I might do that look suspicious, to make their morning more interesting, but I don’t think my imagination had managed enough sleep.

I am not going to sugar coat this. I kept going to the cafe loo to vomit. In fact I kept having to go and order coffees in various establishments to have somewhere to vomit. I had been up most of the night being sick. I hadn’t eaten anything suspect, and I assume it was a virus. This continued into the afternoon, and once court proceedings started I would race away at less charged moments to be sick.

At 8.30am I went down the Strand to Boots to buy some medicine. On my return ten minutes later, I saw an entire fleet of police vans arrive and park up around Arundel Street, about 150 metres from the court but out of sight.

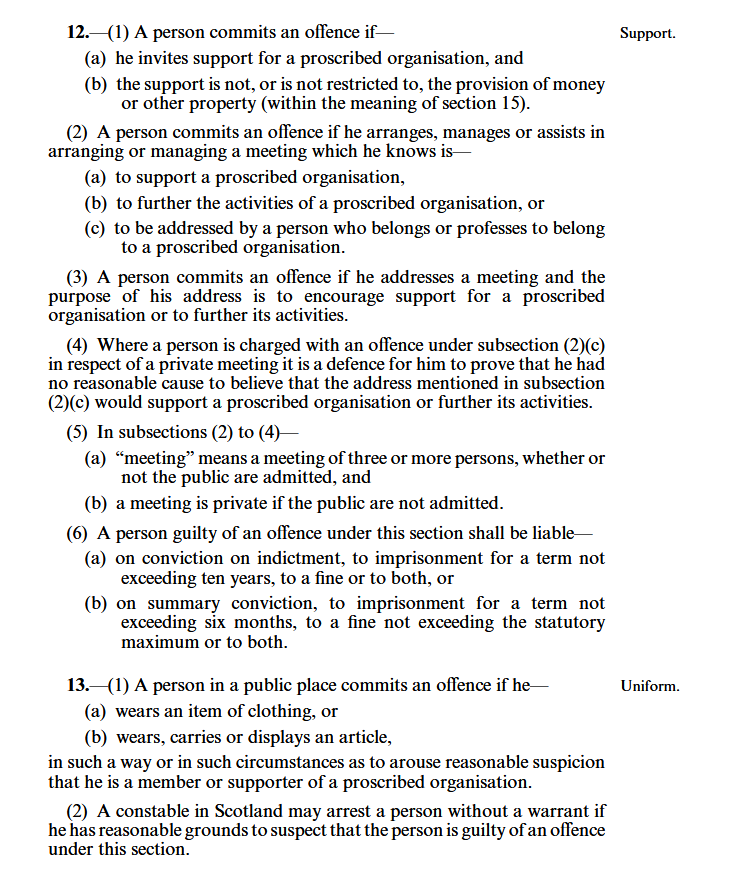

I counted 16 vans and 11 cars. The vans appeared to have 12 to 15 policemen in each. That was only around one side of the court. It was a stern reminder of the issues at stake, and that proscription as a terrorist group gives colossal police state powers. There are penalties of 14 years in prison should you merely “appear to” support a proscribed group, or be “reckless” as to whether you say something that may cause someone else to support it.

This is the Terrorism Act 2000 as originally passed, by the horrible combination of Jack Straw and Tony Blair. It has since been amended to be even worse and make plain that no intent is required – if you “appear” to support, “recklessly” a proscribed organisation, you can be liable for 14 years imprisonment.

For some reason the amended version is not available on the official government website.

At 9am I entered the Royal Courts of Justice. I have spent many more days here than I would wish, and have described the place before:

“The architecture of the Royal Courts of Justice was the great last gasp of the Gothic revival; having exhausted the exuberance that gave us the beauty of St Pancras Station and the Palace of Westminster, the movement played out its dreary last efforts at whimsy in shades of grey and brown, valuing scale over proportion and mistaking massive for medieval. As intended, the buildings are a manifestation of the power of the state; as not intended, they are also an indication of the stupidity of large scale power.”

Well, here I was again. Previously I had only been in the more prestigious courtrooms, off the main hall, courts 1 to 15. This case was to heard in court 73. It was in the East Wing. This required an extremely complex feat of navigation through endless corridors where your footsteps echoed from the vaulted stone ceilings, through uncountable pointed arches, passing open courtyards and cloisters, up stairs and then down.

With every stage the arches got lower, the architraves shallower, the corridors narrower, as you receded from the show of pomp to the mundane exercise of power. By the time you were in the cramped L shaped corridor outside court 73, you might have mistaken it for a 1950’s unemployment benefit office in Solihull.

I was first there but other people started to arrive for the hearing and the corridor became crowded and uncomfortably hot – it was one of the hottest days of the summer. At one point I felt about to faint, and Deepa Driver came to my rescue with a bottle of water.

We were told the court would open at 10.15am. In the ensuing hour I twice lost my place in the queue as I had to leave to go vomit. This did enable me to have a quick chat on the stairway with Gareth Peirce about the prospects for the case.

I managed to get back towards the front of the queue each time, either because of immense personal charm or because people got out of the way as I smelt faintly of sick, you decide. But in the end it availed nothing as only accredited media were allowed into the courtroom.

I am famously not a journalist in the UK, as ruled by Lady Dorrian in the High Court of Scotland, (it’s a long story) so I was not admitted. I was sent instead to an overflow room in court 76 on the floor above, where proceedings could be watched on live screens.

So for this section of proceedings I was not in court. While sound and picture quality were excellent, this was not the same as being in the court itself in terms of picking up the atmosphere and all the little things which the camera does not show. It has never happened to me before in all my reporting.

The hearing was before Justice Chamberlain. He has a liberal reputation. In a case earlier this year, he stated that he had no confidence in statements by MI5.

In cases involving secret intelligence, British “justice” has an extraordinary procedure whether the defendant is not allowed to know the evidence against him, but can be defended on that point in a closed court, without the defendant, by a court appointed barrister known as a “Special Advocate”.

Martin Chamberlain was such an advocate for ten years, and it is impossible for anybody with a slightest modicum of honesty to view a large quantity of intelligence reports without understanding that a high proportion of it is simply inaccurate.

I speak as someone who read an average of perhaps twelve secret intelligence reports every day over a 22 year career.

This is hopeful because the Secretary of State had indicated that in the substantive hearing, there will be intelligence reports on which the government will rely in its evidence against Palestine Action.

It has been widely leaked to the press that this includes intelligence reports that Palestine Action receives funding and backing from foreign states – which really is nonsense.

Justice Chamberlain also ruled against the legality of certain British arms exports to Saudi Arabia if they would be used against the civilian population in Yemen. He has argued for the strengthening of the freedom of speech provisions of the European Convention of Human Rights.

It was therefore not a shock that he was prepared to annoy the legal Establishment by agreeing at least to hear the case as to whether there should be a judicial review of the proscription. He might be the only High Court judge who would have agreed.

Proscribing Palestine Action had been an extremely high profile action by Starmer and Cooper in facing down mounting public anger at the Gaza Genocide, and seeking to restore the zionist narrative that Palestinians and supporters of Palestine are terrorist.

For the court to prevent the proscription from taking effect subject to legal proceedings, would be massive news and a further blow to Starmer’s authority.

So the stakes were very high. Chamberlain gave no indication of this. He appeared enthusiastic to engage intellectually with the subject. He was eager and inclined to muse aloud in his discussions with the lawyers, interrupting sometimes almost out of excitement. He was like a slightly less annoying version of Robert Peston.

Raza Husain KC opened the case for the claimant, Huda Ammori, in the standard form by introducing both teams of bewigged barristers. This took some time as the teams were large – six barristers on each side, while Huda had in addition two firms of solicitors. It was one of the few immediate indicators of the gravity and import of what was happening.

But another was the demeanour of Raza Husain. Normally the smoothest of operators, he rather stuttered into his opening. This struck me throughout the case: Huda’s lawyers sounded slightly detached, not because they did not believe what they were saying, but because they could not believe that we were in a situation that required them to stand there and say it.

Husain opened by stating that civil disobeience has a long and honorable history in the UK. Very often people who had broken the law had been vindicated by history, such as the suffragettes. This was the first time in that long history that a civil disobedience group not advocating violence had ever been branded in law as terrorist.

Five UN Special Rapporters had written to oppose the proscription of Palestine Action, including Professor Ben Saul, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism, who had asked to intervene in the substantive case.

The special rapporteurs identified three fundamental flaws in the UK legislation. There was an overbroad definition of terrorism, an overbroad definition of a terrorist organisation and an overbroad definition of what constituted support for a terrorist organisation.

The overall effect of deprivation of liberty was characteristic of an authoritarian state.

Husain referred to the evidence of Andrew Feinstein. He had experience of the liberation struggle in Southern Africa nad had become an ANC MP. Feinstein testified that Nelson Mandela himself had been designated a terrorist by the British state for decades, and that the anti-apartheid movement used all of the direct action methods used by Palestine Action.

Husain that turned to the evidence of Huda Ammori, who stated that in founding Palestine Action she had been directly inspired by the long history of civil disbedience movements in Britain and the many instances where courts had found such methods, including direct action against the arms industry, to be lawful.

Palestine Action had never included or targeted any violence or injury to persons. Their actions were focused on Elbit, an Israeli state owned enterprise which was fundamental to the Israeli military system. Elbit themselves referred to their staff as “civilian soldiers”.

Husain continued that the proscription of Palestine Action was ill-considered, discriminatory, authoritarian law. It was contrary to both the common law and the Human Rights Act.

For 20 months the Israeli military had been committing acts which most genocide scholars and experts consider to be genocide. The population was now being starved, and the very distibution of humanitarian aid had been turned into a killing field, according to UNRWA.

To say that Palestine Action were committing terrorism was the precise opposite of what they were doing. They were rather seeking to prevent terror and genocide.

At this stage Judge Chamberlain interposed what appeared something of a non sequitur. He asserted that he would have the power to create an order suspending the operation of the proscription to a later date, and that this was accepted by the Secretary of State.

Chamberlain continued that this could be done one of two ways. He cound issue a statutory injunction, or the Secretary of State could submit a fresh order to Parliament. The proscription Order also proscribed two other organisations, including the Maniac Murder Cult, so the suspension would need to be crafted to benefit only Palestine Action.

Judge Chamberlain stated that the need was to do justice or to cause the least injustice to persons affected in the interim should the case be decided the other way. The Secretary of State had not evidenced a national security reason for the proscription to be introduced immediately.

After this apparently heartening judicial intervention, Husain continued that the definition of Terrorism in the Act referred to serious damage to property. “Serious” in this case must be read, as argued by Professor Saul, in relation to international law standards. That was not a measure of financial loss, but damage that threatened further consequences such as to nuclear facilities or civilian aircraft.

The powers of the Secretary of State must be exercised proportionately within (ECHR) Convention rights, such as Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Assembly. Therefore it could be that even if an organisation fell within the overbroad definitions of the Act, it still could not be proscribed.

Judge Chamberlain countered this by citing a Supreme Court ruling in another case (Gould) that overbreadth in legislation can be mitigated by prosecutorial discretion.

[To translate this into plain English, this means that because a law gives the state far too broad a power, it does not mean that the state will choose to exercise that power in all cases. Which gives of course power to the state the power selectively to prosecute only its chosen “enemies” using overbroad legislation]

Husain countered that when the legislation was passed through parliament, the then Secretary of State had given a categorical assurance the power of proscription would never be used against domestic direct action groups. Yet here we are.

Judge Chamberlain responded that to reverse the proscription on the grounds Husain proposed, he would have to demonstrate that it led to an absurdity, citing another case (Hunt).

Husain relied “It is absurd. It is absurd to pronounce a non-violent group terrorist.”

Judge Chamberlain said that what counted was whether if fitted the statutory definition of terrorism, not “some colloquial definition of terrorism”.

Husain said the statute specified that terrorism was designed to induce a climate of fear, influence the government or intimidate the public. None of these applied to Palestine Action.

Judge Chamberlain asked what was the purpose of the attack on RAF Brize Norton if not to influence the government? Palestine Action’s own submissions claim that Brize Norton supplies RAF Akrotiri which is supporting the Genocide.

Husain said that one isolated or sporadic incident did not define the purpose of the organisation, which was to disrupt Elbit and the arms industry. Palestine Action has a non-hierarchical nature. Ascribing responsibility for individual actions was complex.

Judge Chamberlain stated that in December 2024 the UK government had suspended arms licenses to Israel. Could it not be inferred that Palestine Action was attempting to attain this end?

Hussain replied that was not the design of the organisation. It is designed to disrupt the arms supply chain.

He then attempted to make further ground with his next point: documents showed that the Government had engaged both the Israeli government and Elbit Systems in the decision making process to proscribe Palestine Action.

Judge Chamberlain noted that some of these documents were heavily redacted. It was not plain what some of them meant.

Raza Husain referred to a document which involved the phrase “act of vandalism” and reference to “a certain person” intervening. It appeared this process had taken place in March. The decision had therefore been taken before the Brize Norton incident.

Judge Chamberlain asked why it would be unlawful to take into account the views of the state of Israel?

At this point Raza Husain dropped his papers and stared at judge Chamberlain in incredulity. “Israel to interfere? In our criminal law? In our domestic process?”

Chamberlain responded that the government took a range of views into account. Why should it be unlawful to listen to Israel? Husain replied that interference by another state in domestic criminal matters was unconstitutional.

Chamberlain stated that there was nothing in the legislation that precludes taking Israel’s views into account.

Husain again asked incredulously “to decide if it is terrorism?”

Chamberlain responded “They are the victims. They suffered criminal damage.”

Husain said that does not go to the definition of terrorism. Chamberlain countered they could evidence the seriousness of the damage. Husain said he returned to the international definition underlined by Ben Saul. The damage to property had to go the level of endangering nuclear installations or civil aviation. We were not in that territory.

Husain continued that while both Israel and Elbit were consulted on the decision to proscribe, no pro-Palestinian group had been consulted. Judge Chamberlain replied that the statutory basis may preclude any common law right to due process. The Secretary of State had stated that pro-Palestinian groups could not be consulted, because in effect that would give Palestine Action 21 days notice of proscription, in which period it might take pre-emptive action.

Husain responded that may be a claimed reason, but how does it apply the law?

Chamberlain had rather destroyed the flow of Raza Husain’s argument, He now handed over to his colleague Blinne Ni Ghralaigh KC. Readers of my blog last encountered Blinne when she held spellbound the International Court of Justice in the Hague, speaking for South Africa in the Genocide case against Israel.

There the world stopped and held its breath, and the dramatic architecture of the great hall of the Palace of Justice matched the occasion. Here Blinne stood in the much more modest circumstances of court 73.

A plain, three tier dais of utilitarian wood occupied one long side for the judge and clerks. It is the kind of unnatural wood finish that you get on steel legged stacking tables, a peculiarly dark reddish brown with unbroken black lines of grain running straight across.

The bench seats for the lawyers were in the well of the court, four rows of those, and then there was a small platform at the back for the public gallery, containing fourteen seats, occupied by the press, as was the jury box. Everything was the same kind of wood or veneer. Fitted book shelves covered the walls around the court, and a very few contained cloth-bound tomes of law, but it appears that someone had forgotten to buy any books for most of them.

Judge Chamberlain was perched on the top dais of the bench, in a rather austere black gown with a neat pressed linen collar known as “court bands” around his neck, which featured two long tabs of about six inches hanging down in parallel at the front. He rather resembled a Danish Lutheran preacher.

I was in court 76 watching the large screens, as though in the world’s dullest sports bar. The construction was identical to court 73, of the same wood, only the entire thing was three times the size. We observers occupied the well of the court. There was a public gallery of 48 seats which was almost entirely empty.

Had the hearing been held in court 76, everybody could have been in the actual courtroom itself. Why the large courtroom was the overspill court and the proceedings were in the tiny courtroom is an interesting question in itself. The result was that no members of the public were in the actual court, despite their right in law to attend.

I raced out to be sick again before Blinne started, so for her first three minutes I am grateful to the whispered advice of my neighbours.

Blinne was addressing the irreparable harm that would be caused in the next two weeks were the proscription not to be set aside pending the next hearing.

She said that the context of the situation in Gaza was that the Palestinian people there faced annihilation and genocide. The UN Secretary General himself had described what was happening as “A stain on our common humanity”.

The explosive force that had been landed on the tiny area of Gaza was the equivalent of six Hiroshimas. There was firm evidence that Israel was now conducting daily massacres of those Palestinians attempting to obtain food for their families.

Judge Chamberlain interposed that, since December 2024, it is not permissible for the UK to provide any arms to Israel save for F35 parts. Blinne replied “That’s a big “save” when people are being massacred”. There was much evidence of continuing arms supply and other forms of military support.

This massacre is what Palestine Action have been attempting to disrupt and prevent.

If the prpscription goes through, how will you differentiate between Palestine Action supporters and other people who hold similar views and take similar actions?

Irreparable harm will be done to protestors. Some will carefully follow the law. Some will attempt to walk the invisible tightrope on what expressions of support for Palestine are permitted and what expressions are not, and will fall off. Some will openly defy the proscription as an act of civil disobedience, and some live in other jurisdictions, such as Sally Rooney.

This was all the unprecendented impact of the unique proscription of a grassroots protest group.

Three key offences would be created immediately upon the order coming into effect.

It would be an offence to belong or profess to belong to Palestine Action

It would be an offence to invite or to recklessly encourage support for Palestine Action

It would be an offence to arrange a meeting to support Palestine Action or to hear from a member of Palestine Action.

All of these carry up to 14 years in prison.

Wearing clothing or a badge associated with the organisation were offences of strict liability, bringing a six month prison sentence.

Any person convicted would be branded a “terrorist”. A policeman could arrest at any time on suspicion of these offences. They could stop and search. They could enter and search people’s homes and remove property. All of these without a warrant from a court.

Any refugee convicted of any of these offences is deemed a danger to the community justifying expulsion from the UK.

All of this will chill free speech. Those who have supported Palestine Action in the past will fall under suspicion for actions which were perfectly lawful at the time.

Judge Chamberlain interrupted to say that this would not happen; the general priniciple of non-reciprocity would apply.

Blinne said that Palestine Action was a non formalised body. How did you become a member, and how do you stop being a member? How can you prevent being suspected of being a member if you take direct action of behalf of Palestine without any connection to Palestine Action?

Direct action and civil disobedience were not necessarily against UK law. A great many of those charged for direct action by Palestine Action had in fact been acquitted by the courts and therefore their actions had been perfectly legal. There had been few actual convictions. The basic activity was not illegal.

Any organisation, for example “Yvette Cooper”, could be “suspected” by the police of being Palestine Action. [a new pro-Palestine direct action group has been announced named ironically after the Secretary of State].

How would the police decide what showed support for Palestine Action? Were red boiler suits now banned? Judge Chamberlain attempted to pooh-pooh these questions, and Blinne retorted that people had already been arrested for carrying Palestinian flags and wearing keffiyes. There had been an actual trial for carrying a banner showing a palm tree and two coconuts.

What about republishing? What of those who had facebook photos wearing a Palestine Action T shirt that might still be seen? How could you argue for deproscription of the organisation if any mention were likely to bring you under “reasonable suspicion” of support?

Judge Chamberlain replied that in due course he would like to hear the government KC, Mr Ben Watson, address the question of the legality of arguing for de-proscription.

Blinne said that the harm caused during proscription would be irreparable.

Palestinians will continue to be killed while the efforts to disrupt the arms supply to kill them would be banned.

The chilling effect on free speech would be extreme. There were hundreds of thousands of supporters of Palestine Action on Twitter and other platforms. There would be mass mobilisation. Over forty organisations opposed the proscription, including Liberty and Amnesty International (both had representatives in court).

This was a fundamental attack on free speech. Judge Chamberlain responded that they would be able lawfully to advocate for deproscription. Blinne replied that they would not, because this would give rise to the offence of appearing to give support.

Judge Chamberlain asked her to specify which offence was that? Blinne replied that under Section 12, giving intellectual support to the organisation and appearing to support the organisation were both covered.

Judge Chamberlian persisted asking how arguing for de-proscription can be confused with this. Blinne responded that the answer is that nobody knows how it will be applied, and therefore it will chill free speech. The definition of support for terrorism is really widely drawn. It is therefore certainly capable of being interpreted in that way.

What would be the consequences of simply saying “I think Palestine Action did the right thing in protesting the Genocide”? The consequences of straying the worng side of the invisible line were potentially extreme.

Furthermore what would be the position of lawyers acting for Palestine Action in future? Would they be permitted to take instruction? How could they be paid?

In addition to violating Article X of the ECHR on freedom of speech, there was a clear violation of Article XIV on non-discrimination due to the discrimination in selecting a pro-Palestinian direct action group for proscription as, when similar direct action groups concerned with other subjects of protest, such as climate change, had not been proscribed.

According to the Human Rights Act is was unlawful in domestic law to violate the European Charter of Human Rights. Articles X, XI and XIV were all engaged. [Freedom of Speech: Freedom of Assembly: Non-Discrimination]. There was clear Strasbourg case law that neither violence nor financial loss can abnegate Article X and XI rights.

Judge Chamberlain replied that the Secretary of State stated that there was “Significant damage to key national infrastructure” affecting “Components that supply UK and allied forces” and “damage that amounts to hundreds of millions of pounds”.

We broke for lunch, and I reacquainted myself with the bathroom. The sound of my dry retching reverberated around the vast, unflinching stone vaults and halls of the Royal Courts. I trust it was not taken as an expression of support for Palestine Action.

I emerged into the sunlight, and for the first time I saw the large demonstration outside. I did a number of interviews for media all around the world. I had intended to give a quick speech to the crowd explaining what was happening inside, but the protest was extremely lively and involved bare chested young men rapping and a great deal of dancing, so I figured nobody would want to hear from a fat old man in a suit.

Was at Pal Action protest at the Royal Courts of Justice, and surprise surprise who comes out?@craigmurray pic.twitter.com/j4gcAvO8o9

— Matt Ó Branáin #PardonAssange (@MattOBranain) July 5, 2025

There was a massive police presence, and I witnessed two instances of young men being dragged from the fringes of the crowd by the police and searched, for no reason I could discern other than an attempt by the police to provoke a violent reaction that would discredit the protest.

When we restarted at 2pm, Raza Husain noted that the Secretary of State had submitted no argument as to why the proscription had to enter into force immediately.

He continued that the Statutory Instrument proscribing Palestine Action was not to be viewed as having the same authority as primary legislation, and had undergone a very truncated parliamentary procedure. Amendment had not been possible.

It was more properly characterised as an executive instrument subject to parliamentary veto.

Judge Chamberlain agreed, and noted it had also included Maniacs for Murder and had not been possible for Parliament to separate the groups.

Ben Watson KC then rose to argue for the Secretary of State. He stated that the proceedings amounted to a substantive challenge to the proscription itself. But it showed no serious issue to be heard.

Parliament’s intentions are very plain in the Terrorism Act. It sets out clear procedures to add organisations to the list. These had been followed.

The legislation sets out at section 5 the method for appeal against proscription, to the Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission (POAC). The route for appeal is, in the first instance, to the Secretary of State, and in the second instance to POAC.

Judge Chamberlain intervened that when the legislation had been passed, their had been no mechanism by which a court could see secret intelligence. [The inference being this is why POAC was established]. Such a mechanism now existed. At this stage, it was ambitious for Watson to argue that there is no serious issue to be tried by the court.

Watson responded that there is fundamental uncertainty as to whether the court can do this. Chamberlain responded that fundamental uncertainty means there is an issue to consider. The kernel to be addressed today was, are the grounds arguable? If so, what is the balance of convenience?

Watson responded that this case is still narrower than the PKK case. Here there are no fundamental grounds to claim that the order is wrong. Yet the court in the PKK case still concluded that proscription was an issue for Parliament.

This was a constitutional point. Any appeal must go to the Secretary of State first. The issues are precisely the same as in the Tamil Tigers case. All of this is finally in the territroy of POAC. If interim relief were granted, the organisation would not currently be proscribed and so POAC would not be able to look at the case.

In instituting POAC as the route for appeal, parliament had made no provision for interim relief pending appeal, so it plainly was not parliament’s intention that such relief should be possible. This court has no power of judicial review of proscription. Parliament had provided an adequate route in POAC. The first appeal is to the Secretary of State.

Watson was working on the basis of boring the court into submission by repetition. He resembled an insufficiently trained yoga teacher.

Judge Chamberlain asked Watson to confirm that his argument was that if an organisation that clearly does not fall within the definition of terrorism were to be proscribed, they would have no remedy other than to appeal through the Secretary of State, and would remain proscribed while they appealed?

Watson concurred, and went on to argue that if there is an unassailable case that you are doing serious damage to property, then Article X freedom of speech protection is much diminished.

Judge Chamberlain asked whether the chilling efffect on Article X and Xi of proscriptioin, including on people not involved in criminal damage, might be serious. Watson replied that in the Tamil Tigers case it was ruled that the chilling effect on speech on Tamil self-determination does not have substantial weight against the suppression of terrorism.

Watson said that it was difficult for Palestine Action to argue they were not trying to influence government, when they had targeted an RAF base. There was no evidence that consultation with Israel and Elbit Systems by the Secretary of State had amounted to improper influence.

Judge Chamberlain concurred, stating that it was necessary to consult with the victims to assess damage. Watson agreed: it was important to take into account the views of foreign governments in the fight against terrorism. Any argument that the public consultation provision had not been properly enacted could not be sufficiently strong to void the proscription.

Watson said that the fundamental kernel, that Palestine Action is engaged in terrorism as defined in the Act, had not been challenged by the claimant. You cannot grant interim relief on the basis that the definition in the statute is too broad.

The Secretary of State has no obligation to consider the interests of the organisation that is being proscribed. There are no rules on who can make representations to the Secretary of State nor when they should be heard. Parliament did not put in any judicial controls on the Secretary of State. This was deliberate.

Judge Chamberlain remarked that if the justification stands for not giving notice of proscription, that this would allow Palestine Action to make preparations to continue, then the same justification stands for not consulting on the question.

Watson replied that the grounds for objecting to proscription are not substantial anyway so there could never have been any worthwhile representations on behalf of Palestine Action in any consultation.

Watson said that there was secret intelligence evidence about Palestine Action that could be tackled at a later stage through the Special Advocate process. In the meantime what they had was the Secretary of State’s evidence and her statement to parliament.

The police need to be able to implement the law of the land. The courts must not trespass on the rights of parliament, nor appear to do so.

Judge Chamberlain, for the first time, seemed annoyed. “I am not going to worry about that” he said, “you have conceded that this court has jurisdiction”.

Watson said that this was a grave matter of national security, where the courts conceded to the judgment of the executive.

Judge Chamberlain backed down immediately. He said that national security consideration weighs heavily in the scale. “I cannot say that this does not impinge on national security if the Secretary of State says so and that belief is rational.”

Watson continued that POAC is the statutory scheme for appeal,. The public interest represented by the Secretary of State outweighs any private interest of groups or individuals.

Judge Chamberlain agreed, He said the Order exists because the Secretary of State believes it will provide the public with certain protections. If the Order is suspended it will be denied that protection.

The Secretary of State had said that people will be able to continue to oppose Israel’s actions, they will be able to continue to describe those actions as Genocide or other breaches of international humanitarian law.

Judge Chamberlain then suggested that if someone who had once been a member of Palestine Action decided to spray paint on something, that would not make it any more or less lawful than it had been before.

This time Watson refused to agree. He asserted that there can be no private right to do something criminal.

Judge Chamberlain was now enthusiastically strolling around his own fantasy world where the police and prosecutors are kindly and resonable. “There is no reason for anybody to regard somebody’s past association with a now proscribed organisation as blameworthy”, he suggested.

Watson replied that the government’s determination is that the organisation is terrorist. So the existence of stigma is irrelevant. It already exists. The priority is national security. In conclusion Watson spoke the chilling words that made me jump in my chair.

Watson said precisely: “We accept of course that it is Draconian: and deliberately so.”

[Say that to yourself out loud, and consider what kind of state it is where the government can openly say this in court.]

Blinne then rose to rebut. She quoted Andrew Feinstein, that the methods of Palestine Action were identical to those of anti-apartheid activists. Feinstein stated that the majority of Palestine Action activists he had encountered were not terrorists, but pacifists. All of the actions were capable of being protected under Article X and Article XI.

Not every act of damage to property is criminal. There are many examples of Palestine Action activists being acquitted. Judge Chamberlain interjected that they will only in future be illegal if under the aegis of Palestine Action. Blinne retorted that Palestine Action protest outside arms factories regularly. If the same activists turn up to protest, they will be accused of being Palestine Action.

The case of the Tamil Tigers is not apposite, she continued. The Tamil Tigers were engaged in armed action. The Secretary of State had said that all actions of the Tamil Tigers had an axis to violence. That is absolutely not the case here.

Statements in favour of Palestine Action before proscription would be interpreted by the police as giving suspicion of continuing support. What is Palestine Action, other than a loose network of people who want to see Elbit shut down?

The Secretary of State says that somehow people’s Article X and XI rights will magically be protected. This will not be the case. Palestine Action is not being proscribed on the grounds that it rejects the tenets of a democratic society. It rather opposes corporate complicity in fundamental breaches of international law.

There is clear Strasbourg case law that you do not lose protection of the ECHR because of any violent act by another member of the same organisation.

Timing and context are key. Palestine Action are attempting to prevent the most serious crime of all in the middle of a Genocide. In the case of the Christian Democrat Party of Moldova, the Strasbourg court had found it was wrong to ban them without notice just 21 days before an election. Context and timing are important.

People were today protesting outside this court. Those continuing to protest this proscription in the next two weeks would be branded as terrorists were interim relief not given now.

Ben Watson now interjected – I am not sure on what basis – to say that the correct appeal against proscription was through POAC.

Raza Husain then closed for the claimant. He stated that Palestine Action were a group of people who put their bodies on the line between genocide and its planes and weapons.

The Secretary of State had been granted extra time to give evidence of what harm would arise if the interim relief were granted, and she had given nothing. The harm might be the deprivation of liberty to literally thousands of people.

Arrests were forseeable. This was a civil disobedience movement. There will be an I Am Spartacus wave. Civil disobedience is not illegal but has a long and honorable history in British society. It will carry on.

The public interest is indeed engaged. It does not all fall on one side. Hundreds of thousands of people support Palestine Action. There was real and lasting damage to the right of the public to freedom of speech and to protest.

That closed the hearing. It was now 3.15pm on Friday 4 July. Judge Chamberlain said that he would attempt to return with his decision by 5.30 pm.

Outside the drummers were still drumming and the dancers were still dancing. I gave a few more interviews. I really wasn’t feeling well at all at this stage.

At 5.30pm we were back in the court for Chamberlain to give his decision. He started that he had considered the likelihood of success of the appeal for judicial review, and had decided that the only ground where there was arguably a strong case to be heard was that of disproportionate interference with Article X and Article XI rights under the ECHR.

Some of the other grounds may be plausible, but he was not in a position to judge that today.

However he considered that the claimant had not demonstrated that irreversible harm would be caused if interim relief were not granted. Therefore he was not suspending the proscription, which would come into force at midnight according to the Secretary of State’s order.

He assumed that the claimant would seek leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal. He would not grant leave to appeal. However the claimants could try to ask the Court of Appeal for leave to appeal, this evening before the proscription came into force.

Chamberlain then disappeared through the door behind his chair. The legal team were left staring at his detailed judgment.

His incredibly detailed judgment. It is 24 pages and runs to 104 paragraphs, many of which have sub-paragraphs.

Let me try to offer a perspective. I have a reasonable claim not to be stupid. I topped the civil service exams in my year and became the UK’s youngest Ambassador. It has taken me eight solid hours to write this article to this point, not including probably twice that in thinking time.

Chamberlain’s judgment is over twice the length of this article so far. Produced in two hours, at the rate of almost one paragraph per minute? Plainly the bulk of it was written before the hearing – or written by somebody else. Just a thought.

With the disturbing insight that this was all a charade, I joined the Palestine Action legal team who were having to digest this judgment and work out how to launch an appeal to the Court of Appeal after 6pm on a Friday evening.

Otherwise the proscription took effect on the stroke of midnight.

Despite being extremely experienced, nobody on the team had ever been through a similar procedure. Judges are not given to hanging around the courts out of hours, and indeed are strongly inclined to find reasons to wrap up proceedings in trials and hearings early on a Friday. And this was in the middle of both Wimbledon and a Test Match…

Having such a large legal team finally made sense, as they all, including four barristers who had not spoken, scanned through the judgment looking to find grounds of appeal.

Raza gave instructions to telephone the duty clerk of the Court of Appeal and find out if the duty judge were available. The question then was whether the duty judge would be prepared to sit and hear an appeal as a single judge, or would want a panel of three.

The call was made, while we several times had to fend off security guards who were attempting to clear the building. Huda had been giving instructions via videolink, and it was only now that I discovered there was in fact someone from Palestine Action present with the team.

One of the legal team said to me mischievously “If they ask you to leave, we can ask Huda to say that you are with Palestine Action – pause – she had better add until 11.59pm”.

Within five minutes of the call being made, a security guard came to us and told us we were to move to Court 4, the court of the Lord Chief Justice. We had to gather up all the files and move there, a long trek through the bowels of the building, and at one stage diving off on a shortcut up a staircase that nobody in the team knew existed (there are over 100 staircases in this extraordinary building).

We entered Cout 4 at around 7pm. We were now in the grandest area of the building. Forgive me if I recycle a description of this courtroom I have used before:

“It is very high, and lit by heavy mock medieval chandeliers hung by long cast iron chains from a ceiling so high you can’t really see it. You expect Robin Hood to suddenly leap from the balconied gallery and swing across on the chandelier above you. The room is very gloomy; the murky dusk hovers menacingly above the lights like a miasma of despair; below them you peer through the weak light to make out the participants.

A huge tiered oak dais occupies half the room, with the judges seated at its apex, their clerks at the next level down, and lower lateral wings reaching out, at one side to house journalists and at the other a huge dock for the prisoners, with a massy iron cage that looks left over from a production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

This is in fact the most modern part of the construction; caging defendants in medieval style is a Blair era introduction to the so-called process of law – as indeed is the Terrorism Act.

All the walls are lined with high bookcases, housing thousands of leather bound volumes of old cases. The stone floor peeks out for one yard between the judicial dais and the storied wooden pews, with six tiers of increasingly narrow seating. The back of each bench has a little ledge for those behind to place their papers. Watching people attempt to balance laptops on a five inch shelf is quite amusing.”

Gareth turned to me and said that we were honoured to be in such a historic spot, which had already witnessed some of the world’s greatest miscarriages of justice.

As we sat ourselves down, out of the door at the back of the dais appeared in all her majesty the Lady Justice of England and Wales, Lady Carr, who was flanked by Lord Justice Lewis and Lord Justice Edis,

Evidently these three had just been hanging around the court at 7pm on a Friday evening, and happened to be available to hear the request for permission to appeal. I had a moment of crystal clarity. I had spent the whole day participating in a charade, and even the wonderful legal team around me were at base also just participants in that charade.

Lady Carr opened by grumbling loudly that there was very little time, they had not seen the supporting evidence, they had only just received Chamberlain’s judgment, and had no idea what were the purported grounds of appeal. She asked Raza Husain if he had grounds of appeal, and what were they?

She reminded that an appeal was not a rerun of the case but had to find specific errors in law by Judge Chamberlain. “Where do you say that he erred?”

Raza Husain evidently had not been expecting to present the grounds of appeal instantly, and the team had only just finished reading the judgment and started thinking about how to appeal it when we had been called to Court 4. He was now instantly standing in front of the Court of Appeal.

He extemporised that there were three grounds of appeal at least. The judge had erred in law in that he had failed to take into account the weight of mass arrests in assessing the balance of convenience argument. He had failed to insist upon evidence of the urgency of immediate imposition. He had failed to accord due weight to the failure of the Secretary of State to consult before proscription.

Lady Carr said that the court would hear an app;ication for permission to appeal. Skeleton argument for the appeal must be submitted in one hour, by 8.15 pm, and the court would hear oral arguments at 9pm and endeavour to deliver judgment before midnight.

This was somewhat confusing. They were granting a hearing for permission to appeal, not agreeing to hear an appeal. So if they granted permission. there would have to be a further stage of the actual appeal hearing. How could that be done if their decision on permission to appeal were not given much before midnight?

There being no time to retire anywhere else, the legal team starting beavering away immediately on the benches. At 9pm we were listening to the appeal.

Raza Husain said he would make five very brief points.

1) Civil disobedience had a long and honorable history in the UK

2) This was the first time a non-violent direct action group had been proscribed as terrorist

3) Five UN special rapporteurs had written opposing the proscription

4) Huda Ammori had been inspired by the suffragettes

5) Andrew Feinstein compared the methods of Palestine Action to the liberation struggle against apartheid

And there were five grounds of appeal

1) The judge had erred in law in saying that there would not be substantial irreparable harm if the proscription were not delayed. There were undisputed consequences of arrest for expressing support for Palestine Action – this harm was deprivation of liberty, loss of employment and stigma

2) The judge had afforded insufficient weight to the up to 14 year prison sentence for simply stating “I support Palestine Action”.

3) The judge had given undue weight to national security considerations, where no evidence of urgency had been given

4) Blinne took over for Ground 4. Chamberlain had erred in law in failing to take proper account of the impact of Articles X and XI of ECHR.

Lady Carr interjected that Chamberlain did say there were Article X and XI grounds for the application for a judicial hearing against proscription. Blinne responded that however he had failed to give this sufficient weight against national security in the balance of convenience exercise, and that he had erred in saying that future evidence on this will be forthcoming from the Secretary of State. He had to do the balance of convenience exercise on the evidence before him, today.

If the proscription order came into account, it would have a chilling effect on protests outside Elbit factories, even from people unrelated to Palestine Action. It would chill free speech on Palestine. Any action for Palestine might be claimed by the police to be support for Palestine Action, and people would be jailed on remand.

Palestine Action was an extremely loose organisation. What constituted support was extremely unclear in such a case, and there could be hundreds of arrests.

5) Raza Husain took over again for ground 5. The availability of an appeal to POAC does not oust judicial review, There were consequences for the common law right of free speech and for articles V and X of the ECHR.

Ben Watson stood to respond for the Secretary of State. He said Chamberlain’s judgment was measured and detailed. The claimant in this appeal had not challenged Chamberlain’s finding that the Secretary of State had rightly designated Palestine Action as concerned with terrorism.

They had not appealed against the crucial argument of the public interest in allowing the law of the land to take effect. Their criticism of the judge’s decision goes only to weight afforded to varying factors, on only one of the strands which the judge was balancing.

The court could not give weight to the threat of mass flouting of the law. The claimant was merely attempting to relitigate matters which had been properly considered by the court.

Chamberlain said that there was a serious issue to consider under Article X and XI. That is not the same as saying there was a strong case. The judge was not depending on future evidence, he was merely indicating that further evidence might come.

Lord Justice Edis asked Watson how he responded to the argument that not all members of an organisation should be held responsible for the actions of an individual. Watson replied that Palestine Action were responsible for a long pattern of criminal activity.

On rebuttal, Raza Husain said there had been no denial that the judge had failed to weigh the correct counter-factual against Article X and XI. Political speech on Palestine is protected speech. It attracts significant Article X protection and must continue to do so.

Blinne added that the appeal is not about what will happen to people engaging in unlawful conduct, it is about what will happen to people who are engaging in conduct which would be perfectly lawful were it not for the proscription. That is how the effect on Article X must be measured.

This was the first ever proscription of a non-violent movement. The harm was that it would criminalise the article X protected actions of law abiding people.

That concluded the appeal, at about 9.30pm.

In less than an hour the judges were back with their verdict. Again it was available in writing, and despite Lady Carr made a point of fussing about typos due to the haste, I quite simply do not believe that is was produced in under an hour. It contains 52 paragraphs, some of which have many sub-paragraphs.

It is possible to make an argument that Judge Chamberlain had pre-written most of his judgment based on the documents and skeleton arguments that had been submitted in advance and only had to make some amendments to reflect the oral hearing.

But the Court of Appeal were supposed not to have known they even had a case until 10 minutes before they sat. I simply do not buy the speed with which these judgements were produced.

Lady Carr set about delivering the judgment. She said that these remarks were just for information; the written judgment was the actual judgment and anything she said did not vary that.

The proscription had followed an attack on RAF Brize Norton. The Order had been passed by each House of Parliament.

Judge Chamberlain had refused to grant a stay of the proscription and had refused to give permission to appeal and had refused any stay pending an application to appeal.

The merits of the decision to proscribe are not a matter for the Court of Appeal. Nor is the court looking into the claims of Palestine Action. The Court of Appeal is only consdering whether Judge Chamberlain erred in law.

On the principle of balance, Judge Chamberlain was right that the court must give great weight to national security and the executive’s approach to it.

Judge Chamberlain was entitled to the view that individual must obey the order while it was in force.

It will remain lawful to express opposition to Isreal or to Israel’s actions in Gaza.

“No person will be prosecuted in relation to conduct before proscription”.

There was no prospect of a successful appeal and permission to appeal was therfore refused.

Raza Ali rose to request permission to appeal to the Supreme Court. Lady Carr responded that plainly that could not happen before midnight. A written application should be submitted by 2pm on Monday.

There followed a horribly display by Lady Carr of sickly congratulation. In response to a correction by Blinne to the accents on her name in the judgment (I don’t know how to do accents on letters in wordpress), Lady Carr gushed about her “lovely name.” She congratulated all the lawyes effusively on being brief and helpful, and said the case “upheld the best tradtions of the bar”.

What it upheld, of course, was a further step into authoritarianism. This was the next morning: an 83 yearold priest arrested for supporting Palestine Action.

———————————

My reporting and advocacy work has no source of finance at all other than your contributions to keep us going. We get nothing from any state nor any billionaire.

Anybody is welcome to republish and reuse, including in translation.

Because some people wish an alternative to PayPal, I have set up new methods of payment including a Patreon account and a Substack account if you wish to subscribe that way. The content will be the same as you get on this blog. Substack has the advantage of overcoming social media suppression by emailing you direct every time I post. You can if you wish subscribe free to Substack and use the email notifications as a trigger to come for this blog and read the articles for free. I am determined to maintain free access for those who cannot afford a subscription.

Click HERE TO DONATE if you do not see the Donate button above

Subscriptions to keep this blog going are gratefully received.

Choose subscription amount from dropdown box:

PayPal address for one-off donations: [email protected]

Alternatively by bank transfer or standing order:

Account name

MURRAY CJ

Account number 3 2 1 5 0 9 6 2

Sort code 6 0 – 4 0 – 0 5

IBAN GB98NWBK60400532150962

BIC NWBKGB2L

Bank address NatWest, PO Box 414, 38 Strand, London, WC2H 5JB

Bitcoin: bc1q3sdm60rshynxtvfnkhhqjn83vk3e3nyw78cjx9

Ethereum/ERC-20: 0x764a6054783e86C321Cb8208442477d24834861a

The post “We Accept Of Course That It Is Draconian: And Deliberately so”. appeared first on Craig Murray.

Source: https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2025/07/we-accept-of-course-that-it-is-draconian-and-deliberately-so/

Anyone can join.

Anyone can contribute.

Anyone can become informed about their world.

"United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

Before It’s News® is a community of individuals who report on what’s going on around them, from all around the world. Anyone can join. Anyone can contribute. Anyone can become informed about their world. "United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

LION'S MANE PRODUCT

Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules

Mushrooms are having a moment. One fabulous fungus in particular, lion’s mane, may help improve memory, depression and anxiety symptoms. They are also an excellent source of nutrients that show promise as a therapy for dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases. If you’re living with anxiety or depression, you may be curious about all the therapy options out there — including the natural ones.Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend has been formulated to utilize the potency of Lion’s mane but also include the benefits of four other Highly Beneficial Mushrooms. Synergistically, they work together to Build your health through improving cognitive function and immunity regardless of your age. Our Nootropic not only improves your Cognitive Function and Activates your Immune System, but it benefits growth of Essential Gut Flora, further enhancing your Vitality.

Our Formula includes: Lion’s Mane Mushrooms which Increase Brain Power through nerve growth, lessen anxiety, reduce depression, and improve concentration. Its an excellent adaptogen, promotes sleep and improves immunity. Shiitake Mushrooms which Fight cancer cells and infectious disease, boost the immune system, promotes brain function, and serves as a source of B vitamins. Maitake Mushrooms which regulate blood sugar levels of diabetics, reduce hypertension and boosts the immune system. Reishi Mushrooms which Fight inflammation, liver disease, fatigue, tumor growth and cancer. They Improve skin disorders and soothes digestive problems, stomach ulcers and leaky gut syndrome. Chaga Mushrooms which have anti-aging effects, boost immune function, improve stamina and athletic performance, even act as a natural aphrodisiac, fighting diabetes and improving liver function. Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules Today. Be 100% Satisfied or Receive a Full Money Back Guarantee. Order Yours Today by Following This Link.